The History of Respirators

Throughout history, people have had to deal with air pollution and smog, owing to excessive coal use in the home and for production, pollution from mining and increased emissions resulting from expanding industrial processes. Since the 14thCentury, London has been afflicted by thick smog, which Londoners came to refer to as ‘peasoupers’. Civilisations learned to cope with pollution by using respirators in one form or another.

The idea of using respirators was pioneered by Pliny the Elder in the first century A.D. when he recommended the use of animal bladder to protect Roman miners from inhaling lead oxide dust. Early inventions did not stop with Pliny as in the 16th century, Leonardo da Vinci, advised the use of a wet woven cloth to protect against toxic agents of chemical warfare.

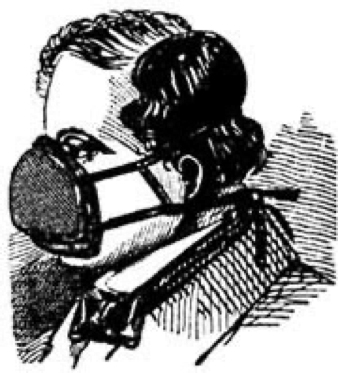

THE HASLET LUNG PROTECTOR ALLOWED BREAKING THROUGH A MOUTHPIECE FITTED WITH TWO ONE-WAY CLAPPER VALVES WITH A WOOL FILTER (OR OTHER POROUS SUBSTANCES TO KEEP OUT THE DUST.

[vc_column_text]In the centuries that followed, inventors worked on designs that have influenced the respirators being used today. The Haslett Lung protector, for instance, which was the first respirator to be patented in the U.S. in 1848, employed the use of one-way valves and moistened wool to filter dust.

[vc_column_text]In the centuries that followed, inventors worked on designs that have influenced the respirators being used today. The Haslett Lung protector, for instance, which was the first respirator to be patented in the U.S. in 1848, employed the use of one-way valves and moistened wool to filter dust.

The Hutson Hurd’s design (picture below) improved on the design of the Haslett respirator and pioneered the cup-shaped mask. Incidentally, Hurd’s air purifying device was in use until the 1970s.

As more scientific minds gained interest in air purifying devices, a race ensued to develop respirators that could protect against a wider range of pollutants, such as toxic gases.

John Stenhouse, a Scottish chemist, built the first respirator capable of capturing toxic gases from the air. His designs pioneered the use of charcoal in a wide variety of air purifying devices, including respirators used by firemen.

Inventions after the first world war

After the first world war, the military took a keen interest in the use of respirators as a defence mechanism against chemical warfare. This, in turn, led to the creation of efficient and inexpensive filters in the 1930s, that were made with resin-infused dust. Further developments led to filters made out of very fine glass fibre, that could eliminate particulate matter while providing little resistance to breathing.

LONDON SMOG IN NOVEMBER 1953

In the years following the First World War, countries such as the U.S and U.K were faced with some of the worst air pollution cases in history. In December of 1952, the city of London was afflicted by a thick layer of smog, which lasted for five days and resulted in 12,000 fatalities and 100,000 reported cases of respiratory tract illness. Known as ‘the great smog’ or ‘big smoke’, it was caused by the overuse of coal, coupled with extremely cold weather and lack of wind. In 1943, Los Angeles also suffered from its first smog incident. LA’s massive vehicle industry and factories were to blame for the smog. These cases would give impetus to environmental law reforms and a greater sensitivity to pollution issues. Labour reform laws also paved the way for the development of more efficient respirators to be used in the industry.

Although modern devices that were created following these and other pollution cases were more sophisticated in design and in the materials they used, they still fall in two main categories that are reminiscent of pioneer respirators:

- Air-purifying respirators: these purify the air by removing pollutants before they are inhaled.

- Air-supplied respirators: which deliver fresh air from an alternate supply.

What the future holds for respirators

New Delhi in India, Tehran in Iran, Mexico City in Mexico and most Chinese cities continue to suffer from heavy smog. The demand for respirators will continue to rise, but not so much in the developing countries that have strict anti-pollution regulations, but in countries that are still developing, or that don’t have well-structured legislation for controlling air pollution.

Another trend has emerged in countries like Japan, where young people are using masks as a fashion accessory. As one study predicts, further attempts to develop respirators will be centred on fit, comfort, mood and performance.

It’s worth noting however that though respirator technology has come far, most people still wear more primitive forms of respirators, such as surgical masks, due to limited knowledge of the composition of pollutants and how respirators work. This highlights the need for raising awareness to ensure that people are wearing masks that will eliminate microscopic particulate matter that cannot be eliminated by surgical masks.